Sam Gordon writes from Nicaragua on the history and prospects for the Sandinistas

The decade of the 1980s was hard time for the political Left. Britain had the Thatcher government; the USA had Ronald Reagan as president. After him George Bush continued the Republican Party rampage. In South Africa the Apartheid regime was slaughtering black people on its own streets. In South America the dictator Pinochet was consolidating his rule in Chile and the generals of Argentina had been “disappearing” people they didn’t like for some time.

At the end of 1981 Ronald Reagan fired 11000 USA striking air traffic control workers. British print workers fought a rearguard action against Rupert Murdoch’s News International and the London Metropolitan Police. Elsewhere in the country police forces fought members of the National Unions of Mineworkers on picket lines during a year long strike. It all ended up rather badly for the trade unions.

In defiance of many British Labour Party members the parliamentary leadership opened the door leading away from social democracy and towards neo-liberalism. Party leader Neil Kinnock, often with eloquent oratory, boasted about his council house upbringing and working class roots. But he was no match for Margaret Thatcher, daughter of a grocer and unheard of Conservative councillor who lived above the shop. History records that the handbag truly trumped the windbag.

A more radical political Right advanced. Its campaign not solely confined to domestic policy. The post Second World War consensus, with a voice for the poor, was declared no longer fit for purpose. In this new world order the Non Aligned Movement (NAM), a gathering of poorer nation known as the G77 and the United Nations funded United Nations Council for Trade and Developed (UNCTAD) became part of a lost legion. The once influential voice of Liberation Theology – putting forward “God’s option for the poor” in the Catholic Church of Latin America was swept aside.

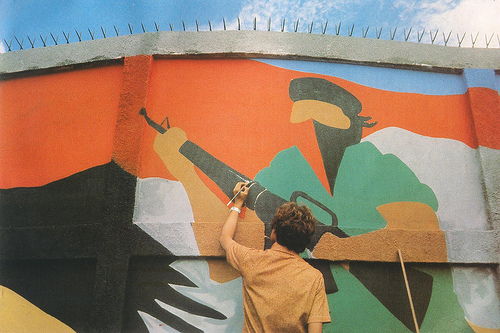

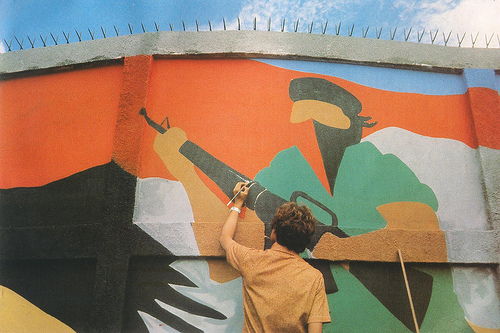

Nicaragua

In all this doom and gloom a lot of people, not only the committed Left, found a silver lining. That was the example of Nicaragua. The appealing sparkle of this small Central American republic didn’t only attract other Latin Americans. It caught the attention of people from Asia, the Arab world, Australia, North America and Europe. Scotland had its own Scottish Medical Aid for Nicaragua, a Non Governmental Organisation (NGO) specializing in health and education.

Much has been written about Nicaragua. The struggle of its people against the 30- plus- year Somoza family dictatorship, followed by a war on its democratic survival waged by dissatisfied Nicaraguans with training, support and funds from the USA, known as the Contra War. (Contra is Spanish for against). All this is a matter of public record. But the euphoria that accompanied the struggle of the 1980s has died away. Many First World Nicaragua activists of that era have moved on to other fronts of interest. And, truth be told, among many on the Left there is also a sense of letdown, even betrayal by those who led the Sandinista Popular Revolution of 1979.

My objective here is not to refresh the memory of readers concerning recent Nicaraguan history. Nor is it to point out the various, perceived or otherwise, failings, short comings, and sell outs that have so disillusioned and perplexed the Left. What I do hope to achieve is to place contemporary perceptions of Nicaragua today in a relevant context. From there, perhaps we might be better informed about the future options history will present to us.

A Starting Point

Nicaragua is a country with a distinct political life and tradition. Since 1979 there have been three main political camps. The oldest gathers around the green flag of conservatism. Stronger in the southern, Pacific side of the republic, its appeal is found among those favoring the big latifundista or land owners, with an inward emphasis on the economy and the acceptance of an old and establishes social order. A place for everyone, where everyone knows their place.

Growing out of that have been various liberal parties. Historically their strongest support has been based around the northern regions of León and Chinandega. They gather around the red and white flag and are much more inclined towards an export led economy. It wouldn´t be too far off the mark to say they represent “new money” while the conservatives come from “old money.” The truth is that a lot of the new money families that dominate much of party political and economic life come from long established families that were once conservative.

Many of Nicaragua’s problems today stem from the fractious period of the mid 19th century. Then, both tendencies locked horns in debilitating squabbles and civil war. Opportunities to advance the nation state, even in a nationalist sense, were squandered by warring factions of the ruling classes. Interference from the USA further aggravated this.

The third political force in Nicaragua today is Sandinismo. The name comes from Augusto César Sandino, who had worked as a mechanic in the Mexican oil fields. Under a red and black banner and rejecting Marxism, he led an army, during an insurgency war in the 1930s. Some of this tradition continues in the form of the Sandinista Front for National Liberation (FSLN), created in the 1960s. It is the largest single political party and is capable of mobilizing support from large sections the rural and urban poor.

Apart from these principal players there are other supporting roles to consider in the political drama. A good many people who were Sandinista activists during the 1980s no longer regularly engage in political activities. Liberalism has a number of different parties that seem unable to settle their differences. A splinter group from the FSLN also exists (1) as does a small party with roots going back to the Contra movement (2). Political parties with bases solely in the autonomous regions of the Atlantic coast make up another component.

At one time Nicaragua claimed over twenty political parties all vying for a voice in the National Assembly. Today, essentially, there are two competing groups; the ruling FSLN and the Liberals. Off stage, other acts come and go lending their own contribution to the political drama. A number of NGOs exist, often promoting a political agenda. Special interests, rights and pressure groups operating under a banner - their banner and one much used by commentator s- of Civil Society are both visible and vocal.

The Triumph Lost?

An armed struggle, which eventually drew active support from the wider Nicaraguan population, took much of its inspiration from the Cuban example of 1959.(3) On 19th July 1979 the Sandinista forces entered the capital city of Managua. Nicaraguans still refer to this as La Diecenueve, The 19th. But the political significance of time is best summed up as El Triumfo, The Triumph.

The Triumph of 1979 set out a bold thesis. Disbandment of the dictator’s armed forces, redistributive land reform, health services and education made accessible on a scale never seen before in Nicaragua, a new constitution, women in key government and administrative positions and other progressive reforms.

Agricultural cooperatives were set up, in line with Sandino’s original aspirations. Work brigades bolstered by young volunteers from the city helped harvest Nicaragua’s principle export, coffee. A wide range of skilled workers in health services, technical and higher education as well as areas of industrial and administrative expertise arrived from all over the world, often with their government’s direct or indirect support.

This was enough to evoke the wrath of the USA which trained and equipped the right wing, counter revolutionary Contra. The ensuing armed struggle took on the characteristics of low intensity warfare. It was successful in distorting the national economy and contributing to community tensions. Yet despite what the government in Washington said about the threat of communism down south in its back yard, large, medium sized and small privately owned businesses continued to struggle and survive in revolutionary Nicaragua. This war and many of the social programs officially ended when the FSLN, in the grip of war induced stress, lost the elections of 1990.

The loss of the Sandinistas has been explained away by some as a general tendency that was marked by the fall of the Berlin wall, the reunification of Germany and the collapse of the Soviet Union. The latter’s collapse came a year after the Sandinistas lost the elections.

This European attempt at socialism has been largely consigned to history books, with the odd derogatory comment by journalists of left and right persuasions, when hard pressed to give an explanation of unfolding history. But in this part of Central America Sandinismo clings on in the form of expanded health and education services, cooperative and women’s movements and a body of social aspiration not satisfied by neoliberalism.

Many commentators have said that Violeta Chamorro, the UNO candidate who won the elections, ended the war.(4) An alternative take on this would be to say that the Contra war ended in 1990, not because Violeta won, but at the same time, because the US deemed it unnecessary to support, supply and train the Contra. In the peace that came after the war a train of ideas and practices set in motion, rolling back the thesis of the Sandinista Popular Revolution.

Moving On - Going Back

To the mid 20th century populist British Conservative Prime Minister, Harold MacMillan, is accredited the saying; “don’t fall out with the Brigade of Guards (elite British military regiments), the Catholic Church or the National Union of Mine workers.” As a paradigm of British governance this lasted into the early 1980’s. That was when Thatcher and Reagan went on a union busting spree. It coincided with a related shift in US foreign policy.

As far as the US military establishment of the 1980’s was concerned communists were everywhere, particularly in southern Africa. Cuban solders with old Soviet tanks and other military equipment arrived in Angola to fight alongside the MPLA who were up against the Apartheid army of South Africa.(5) There were other threats in the region. Besides the African National Congress in South Africa, there was SWAPO (6) in South West Africa (now Namibia) and FRELIMO (7) in Mozambique. In Washington, policy makers turned from “containment” of communism to a “rollback” mode.(8)

This was the world of the 1990’s into which Nicaragua was thrust after years of dictatorship, guerrilla war, foreign military and economic intervention in their domestic affairs. The Sandinistas had presented their brave new thesis to the world. But the piper was playing the tune of structural adjustments paid for by the International Monetary Fund. The First World began celebrating the antitheses of the 1980’s.

In the Background

In his book, Eurocentrism, the Egyptian economist Samir Amin devotes considerable attention to metaphysics; its role in what he calls a tributary culture and its decline in the advance of capitalism. The tributary system Amin refers to takes in Europe but stretches well into Asia as far as India and China, the Arab world and much of Africa. In the Atlantic countries of Europe this is usually called feudalism. Amin, a Marxist, does not deny nor diminish the rise of capitalism in Europe but consistently argues the case for the understated economic, social and cultural development of Africa, Asia and Latin America.

At the end of the 15th century Columbus opened the doors of Central America to European migration. With it came the political perspectives and social attitudes particular to that time period. And the main vehicle, navies and armies apart, for transmitting these influences and structures was European religion, nothing less that the Catholic Church. At the core of the church, along with its doctrines and liturgies, snuggled close to spirituality was metaphysics; dimensions of reality that exist beyond the physical world which yet form part of human experience. Following Amin’s lead, a brief journey along the metaphysical route taken by Nicaragua may be worthwhile.

No visitor here will escape the importance of Christian beliefs in Nicaragua. Humble gathering places and modern temples of Protestant evangelism proclaim a variety of Christian interpretations. Baroque churches testify to the continuous, if somewhat challenged continuity, of Roman Catholicism. Street processions commemorating the Virgin Mary and a host of other honoured catholic dignitaries and saints are part of everyday life.

For many in Nicaragua saints are seen as a dependable entity. An actual example I know of will serve to illustrate this point. During a difficult labour a pregnant woman prayed to Saint Martin for help with her delivery. When the baby was born, presumably with the beneficial intervention of Saint Martin, the saint was duly honoured. The child was named Martin.

Unlike North America, in Nicaragua, there was not the same continuous flow of migrants during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The northern migrants brought diversity in language and cultural experience and a wider set of skills and knowledge in manufacture, commerce and intellectual traditions. In Nicaragua during the same period there was less industrialisation. It did not have the same volume of external and commercial influences as Panama, Costa Rica and El Salvador.

With the arrival of Europeans in Central America the seeds of capitalism were scattered and husbanded. In Nicaragua’s fertile land it grew and flourished, but unevenly. The few who controlled coffee, sugar, fruit, basic grains and to a lesser extent beef production, doubled in the role of political elites. In these brutal conditions the social order was established and maintained by the rule of the caudillo or strong man. Like other parts of Latin America, capitalism developed in what an advisor to Chile’s Salvador Allende, writing about modern industrial management, has referred to as conditions of low variety; that is, options were few.(9)

For those on or beyond the margins life was precarious. Paid work, was seasonal, casual, not well rewarded and at the whim of the patrón, or master. In the material and social world of ill-developed capitalism, dependency was pervasive. Metaphysics reflected this reality. If good fortune came it was a case of ojala. This is a Spanish word derived from Arabic, which literally means, “If Allah wants it.” In Catholic Nicaragua, for Allah read; The Virgin, Heavenly Father, or any number of saints.

After what was regarded as progress during the 1960s and 1970, the NAM, G77, and UNCTAD began to wane. Much of the First World Left did not recognise this for what it was; a systematic attack on opposition to the “reproduction of capital.” In other words, it was the advance of imperialism. Amin sums it up like this, “The collapse of the Soviet Union system also entailed the collapse of the social democratic model . . .” (10) There are still Social Democrats but the parties which laid claim to that tradition have broken faith and adopted neoliberalism. Who could the wretched of the earth now turn to if not to themselves?(11)

A Revolutionary Return?

First Lady Rosario Murillo, Coordinator of the Communication and Community Commission has described the present electoral period as the second stage of the Sandinista revolutionary government. This view has been reinforced by her frequent use of such phrases as; “the Nicaraguan family” and “Nicaragua - Christian, socialist and in solidarity.” This is a linear view of history.

A more dialectical portrayal of the present FSLN government might be expressed differently. In this case the present, the here and now, is a product of past activities and beliefs. The present is a working out of a future that has not yet achieved definition. It is a synthesis, not an end game. It is the preparation of a new thesis. This begs a number of questions. Does the future of Sandinismo reach for the right or the left in political terms or will it wither on the vine. Will it follow the way of the caudillo or be inclusive and participatory? Above all, does it have the desire and capacity to be a transforming political force? That is, facilitating a radical and popular shift in power.

Some say the FSLN, with President Ortega as general secretary and his wife as the public voice of government, is already taking on some of the characteristics of the Institutional Revolutionary Party of Mexico. A view expressed by Monica Baltodana (12). The term “Ortegaismo” has been coined to describe what some see as the Ortega family’s high profile in state and commercial affairs. Another view claims that party, and therefore Ortega loyalists, have been placed in too many positions of national, municipal and civil society administration. No party occupies elective space to the left of the Sandinistas.

There are distant similarities to the populist presidency of General Juan Perón of Argentina during the 1940s. This saw social and welfare benefits for trade unionists and the urban poor, while “Peronista” officials were awarded key administrative positions. Sometimes images of Nicaragua’s presidential couple, sat at table with high ranking military and police officers, Sandinista trade union leaders, a cardinal and bishop of Managua are reminiscent of General Franco in Spain.

A Change of Colours

It was a matter of some public knowledge that Manuel Calderón, mayor of the university city of León, did not have a good working relationship with Rosario Murillo. But it did come as a surprise when the FSLN political secretary of León delivered a demanding message from the First Lady to the mayor; that his anticipated resignation was not a matter for negotiation butone of immediate effect.

Manuel’s brother, a local catholic priest, organized a mass for the dismissed mayor, in the Church of the Hermitage. His sister, an official of León’s municipal theatre took a more dramatic and colourful approach. She announced on air, “me hermano es rojo y negro, no chichi / my brother is red and black, not pink.” Chicha is a cheap soft drink made from ground maize, sweetened with sugar and made an insipid pink with artificial colouring.

In the election campaigns of 2006 and 2011 pink banners replaced some, but by no means all, of the old red and black. The colour has become synonymous with Rosario Morillo who is credited with managing both victorious campaigns. Rosario has become increasingly identified as the voice of government and people have quietly speculated that she could be the FSLN presidential candidate in the 2016 elections. She does not hold any elected position at present.

Civic Concerns

The Sandinista government has introduced a number of programs aimed at combating poverty, which few believe the Liberal opposition would have undertaken. Zero Hunger, Zero Usury, and Dignified Housing are just some of the social programs set in motion by the FSLN government. The purchases of Venezuelan diesel and petrol through ALBA have ensured that transport runs, services are delivered and the wheels of private industry keep turning. Yet, as with any democracy concerns have been voiced about those who hold public office. Sometimes the concerns are ephemeral or easily abated; others are more persistent. Below are listed some of the more notable concerns that have surfaced since the FSLN lost the 1990 elections.

Govern from below 1990

In a speech following the 1990 election loss Daniel vowed to keep “ruling from below” a reference to the power that the FSLN still wielded in various sectors. He also stressed his belief that the Sandinistas had the goal of bringing “dignity” to Latin America, and not necessarily to hold on to government.

“We will govern from below, we will govern from below, and we will govern from below. We will defend from below, we will defend from below”, he said at some length to the cheers of enthusiastic supporters.(13) The voters had decided that they did not want him to govern; that was clear. Although, he certainly retained the democratic entitlement to defend from below.

La Piñata 1990

A piñata often appears as a birthday treat. A cardboard mock up, usually in the form of an animal, the piñata is suspended from the branch of a tree or a beam in the roof of a house. An adult controls the height and swing of this with an attached rope. Young children then take turns to swipe at the piñata using a stick or base ball bat. To add to the fun the child is blind folded and the other children scream instructions; up, down, behind, etc. When the piñata has been battered to destruction sweets fall out and the screaming kids get into an unsightly scramble for the goodies which have fallen to the floor.

After the shock of losing the 1990 elections the word piñata entered into the political vocabulary of Nicaragua. The state had confiscated lands from Somoza collaborators and sympathizers, many of whom had fled to Miami. Cuba had donated a complete sugar refinery to the government. What to do with these resources? It was widely believed, and with good reason, that the new government would either pocket or privatize these resources. So, much was dispersed to FSLN members for safe keeping, until the return of Sandinismo. That’s when the word piñata became political.

Zoilamérica 1998 - . . .

In the early days of March 1998 an event took place that in its own way was as shuddering as an eruption of one of Nicaragua’s many volcanoes. Zoilamérica, daughter of Rosario Murillo and adopted step daughter of Daniel Ortega, proclaimed to the world that she had been sexually abused as a child by Daniel over a period of many years. Commentators went into overdrive. Some claimed that this revelation followed a typical pattern of someone who had suffered prolonged sexual abuse. Zoilamérica, then 30 years of age, was denounced as a CIA plant, and worst of all, a sociologist. For others, presumption of innocence until proven guilty was a non starter.

Since then Zoilamérica petitioned the National Assembly to have Daniel’s parliamentary immunity to prosecution set aside so he could be prosecuted in the courts. The National Assembly which had a male majority refused to include the petition on its agenda. Through a Nicaraguan NGO, the Nicaraguan Human Rights Centre, she then filed a suit with the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights (IACHR) claiming denial of justice. In 2001 the case was declared admissible. Soon after, Daniel agreed to stand trial. But the judge said the case was closed as the statute of limitations – time limit in legal terms – had been exceeded. The following year the IACHR’s suggested both parties find a “friendly solution.” This was accepted. In 2003 Zoilamérica abandoned this legal avenue.

The family tragedy continues to rumble into farce.

El Pacto, Therapeutic Abortion, and More

In 1999 Daniel Ortega and Arnoldo Aleman, Constitutional Liberal Party leader, found common ground. This became known as “El Pacto”, The Pact. Agreement was reached on what percentage of votes, given certain margins, would permit a particular presidential candidate the right to take office. There was also agreement on quotas of officials, with known political positions, holding key posts in the Supreme Court and the Supreme Electoral Council. This scandalized many Nicaraguans at the time and continues to exercise commentators. It has entered into the everyday currency of how political business is done in Nicaragua - from below. Today it looks like the FSLN has done rather well from El Pacto, with apparent control of important state institutions. Daniel Ortega won the presidential election of 2006 with less percentage vote than he lost the pre-Pact elections of 1990.

The right to what in Nicaragua is referred to as therapeutic abortion – termination of pregnancy when certain conditions were determined – existed on the statute books for over a hundred years. Before the 2006 election both Catholic and Protestant evangelical churches campaigned to change this law and deny women, under any circumstances, the long standing right. In the National Assembly the churches had their way. No Sandinista and few others, voted against the new law.

There are a number of other agreements and convergences affecting public life at national, municipal and community level.

The Future Begins Today

It’s been clear for some time that many national liberation movements of yesterday have succumbed to the interests of global capitalism. South Africa, Mozambique and Angola have all embraced neoliberalism and this has come to pass under governments of national liberation parties, claiming left credentials. The compliant position of Western governments and electorates has already been mentioned.

Given that, it’s reasonable to ask if Left political movements and those of us who support them really have any idea of where we want to go. What is “the world we want to see”, of which Amin writes? It should come as no surprise that there is a certain fogginess at this stage of history. One of the most successful strategies employed by today’s capitalism – aided by its cheerleader politicians and journalists - has been to convince us that neoliberalism is without ideology. It’s a question of, “that’s just the way things are.” Lost in the fog also is the influence of sections of the European Left which took such pride in its refined analytical capacity. The old Soviet Union was variously declared; real socialism, a degenerate worker’s state, a deformed worker’s state, state capitalism, a workers’ state with bureaucratic deformations . . . . Political parties, not to mention pubs, were so defined. The search for ideological exactitude in human behaviour can be exasperating at times, not to mention beneficial to the Right.

In Nicaragua Sandino is proudly remembered for his words, “Only the workers and the peasants will go all the way to the end.” Yet when he rejected Marxism in the 1930’s he also stepped back from any ideological identity. Some say he was of the anarcho-syndicalist tradition. The general was influenced by mysticism and had some contact with mystical and spiritual organisations.(14) An accomplished organiser, insurgency soldier, and inspirational leader, he left behind a political tradition favouring the poor. But he left little by way of a body of political ideas with economic and social structures on which to build a system of governance. Almost 80 years after his death his latter day followers seem to have little in the way of an ideological compass. Indeed, it appears to be the case that the die has already been cast to present Daniel Ortega as the party’s candidate for president at the 2016 elections. Not for the first time, questions of internal democracy and personality cult are raised.

The expression of ideology might be written up in libraries or drafted during conference discussions. But the ground work is done by men and women struggling with the powers that be and interacting with each other. Just now all seems quiet in Nicaragua. It’s almost like Yeats said, “The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity.”(15) Another internal challenge is to increase the variety of political options available to a long suffering people. The MRS has emerged from a section of a previously existing political class. Outside of those who have at one time or another come through the university education process, this party has at best patchy support among the popular, urban based classes. Daniel and the FSLN are seen as representing stability. That is pleasing to some, particularly those in government backed employment. For those not so fortunate the situation described as stable is seen more as stagnation; no work, little prospect of work unless they are identified as FSLN supporters, work that is often poorly paid.

Further away, the Arab Spring is still a work in progress. But it does show that mounting discontent will eventually have its day. Contrary to what the opposition to the FSLN often claim Nicaragua is not under a dictatorship. Neither is it a country which lives and breathes contesting political ideologies. Marxism is seldom spoken of; since the 1980s socialism seemed to have been forgotten until Hugo Chavez put it back on the agenda. But Nicaraguans, even at the level of formally uneducated and relatively uninformed poor, will speak of what is fair and just. Students, pensioners, transport workers and retired solders have all taken to the streets in popular protest during recent years. How the Sandinista government handles this discontent will affect the balance of support it can expect at the polls.

In a wider world, at least in Latin America, Fanon’s “wretched”, are awakening with new options. This is principally through the creation of structures such as ALBA – which is the Spanish word for dawn. Are Nicaragua’s old leaders able to rise with a new dawn, capable of stretching beyond stability and moving state and society along the road of transformation? Right now it looks like the present leaders, safe with apparent stability, have travelled as far as their hearts and minds permit them to go.

Notes and References

- In 1995 a new party split off from the FSLN calling itself Movimiento de Renovación Sandinista /Sandinista Renovation Movement (MRS).

- Former members of the Contra, their families and sympathizers stopped using the name Contra and formed a political party called the Partido Resistencia Nicaragüense / Nicaraguan Resistance Party in 1993.

- Zimmermann, M. 2000 “Sandinista Carlos Fonseca and the Nicaragua Revolution” Duke University Press Chapter 3 The Cuban Revolution 1958-1961

- Unión Nacional Opositora/ National Opposition Union (UNO) A group of opposition parties from the right, centre and left of Nicaraguan politics formed to oppose the FSLN at the 1990 elections.

- MPLA Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola / People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola

- SWAPO South West African People’s Organisation

- FRELIMO Frente de Libertação de Moçambique/ Mozambique Liberation Front

- Pashard. Vijay, 2012 “The Poorer Nations- A Possible History of the Global South” Verso Page 112

- Espejo, R. Harnden.R 1989 “The Viable System Model – Interpretations and Applications of Stafford Beer’s VSM” John Wiley and Sons Page 56. Stafford Beer worked with the Popular Unity government on modernizing Chile’s economy prior to the 1973 military coup.

- Amin, S. 2008 “The World We Wish to See - Revolutionary Objectives in the Twenty-First Century” Monthly Review Press Page 15

- The Wretched of the Earth is the title of book written about the Algerian war for Independence against France. Its author, psychiatrist Frantz Fanon from the Caribbean island of Martinique, was one of the movement’s leaders.

- Friedman, Mike. 020308 Nicaragua: The First Year of the Ortega Government – A Balance Sheet mrzine.monthlyreview.org

- Envio March 1990 Issue Number 104

- Mysticism was having something of resurgence during the 1920s and 30s. Sandino had ties with the Magnetical-Spiritual School of Universal Commune, which was founded around 1911 in Argentina and had followers in Mexico.

- Yates, W. B. 1919 “The Second Coming”

Steve Freeman is a Republican Socialist from England. He recently spoke at the Radical Independence Conference in Glasgow.

Steve Freeman is a Republican Socialist from England. He recently spoke at the Radical Independence Conference in Glasgow.

![Manifestation du Front de Gauche [ 18 Mars , Bastille ]](../../7043/6993357653_b97736aaf5.jpg)