frontline 6

The New Democratic Party and the Canadian Left

In the past few decades, most of the mass reformist parties, especially in the advanced capitalist world, have capitulated to the neo-liberal agenda of the ruling class, often with the acquiescence of the trade-union bureaucracy, and often leading to electoral success. But as Canadian socialist Ernest Tate explains, in Canada the New Democratic Party's (NDP) experimentation with neo-liberalism has induced a severe organisational and political crisis in the party.

At first, openly enamoured with Tony Blair and the Labour Party's electoral success in Britain, the NDP leadership had openly promoted "Third Way" policies, to the consternation of many of its trade-union allies. At the national convention two years ago, however, the leaders hesitated in going all the way in this direction. An openly pro-capitalist grouping – led by Peter Stoffer, an MP from Nova Scotia – had advocated diluting the class base of the NDP by separating the party from the trade unions under a proposal that would have banned both corporate and union donations to political parties. "Disallowing union contributions while millions continue to pour into the coffers of the corporate-sponsored parties would amount to unilateral disarmament," party leader Alexa McDonough had objected. "To undertake such disarmament is madness," she said, setting the limits on how far she was prepared to take the party to the right. The proposal was defeated.

THE NDP AND THE UNIONS

The NDP is Canada's version of the British Labour Party, but on a much smaller scale. Most unions – especially in English speaking Canada – are affiliated to it, either at the national level or through the 2,300,000 member Canadian Labour Congress (which is now in the process of re-evaluating its relationship to the NDP) or at the level of local unions which can elect delegates to conventions. Trade unions account for around 15 per cent of the financial support the party receives on a day-to-day basis. At elections this increases dramatically with "in kind" contributions in the form of full-time staff assigned to work in campaigns. In the last election, for example, the Canadian Autoworkers' Union (CAW) alone raised $1,000,000 in cash for the party, and more importantly, helped guarantee payment to the banks for $3,000,000 of the $7,000,000 loan the party needed; most of the rest was guaranteed by other unions. Even though the party has a capitalist programme and a middle class leadership, for socialists this financial relationship is an important consideration in determining the working-class character of the party. When workers vote for it, their support can be characterised in a historical sense as a break with parties of the ruling class and an expression of independent working-class political action.

Popular support for the party is low. In the last Federal election, October, 2000, it only elected thirteen MPs – a drop from twenty-one – in a lacklustre election campaign that saw its vote fall to around 8.5 per cent. In its history it has never ever been close to forming the Federal government but at various times in its popular support has been sufficient to assume it might one day form the official opposition. In 1993 it elected forty-four MPs. But those days now seem far away, and even though it still has important trade-union and working-class support, there is a great fear in the party that it will not recover from its present malaise. In the past three elections, it averaged just over 9 per cent of the vote.

Members have walked away in droves. Many in Ontario, the industrial centre of the country, with around one third of the country's population, have not renewed their memberships. The party is in deep financial crisis and has been forced to lay off staff. In Toronto, where the party once had a very active base, many constituency associations – especially where there is no elected member either in the provincial government or in Ottawa – meet infrequently, with few in attendance when they do. For the past few years, the only organised left in the party has been the Socialist Caucus (www.ndpsocialists.ca) under the leadership of Socialist Action, who are "supporters of the Fourth International", as they say, but the Socialist Caucus has remained relatively isolated and ineffective, mainly as a result of its primarily propagandistic mode of functioning. Recently, a broader opposition developed in the party, first in the parliamentary caucus, led by Svend Robinson and Libby Davies, two MPs from British Columbia. Robinson had previously contested McDonough for the leadership of the party. Recently, he challenged her support of market-based economics as a solution to society's problems with the comment that the market economy "is a dog that should be put down."

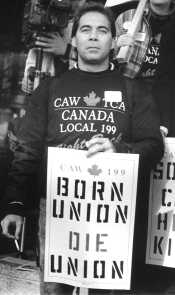

Opposition also came from some of the unions, but mainly from the CAW, through its leader, Buzz Hargrove, who demanded that the party abandon its right-wing shift, arguing vociferously that in Canada there was no space for another "liberal" party and that this would lead to confusion among its supporters about what the party represented and eventually destroy it. He called on the NDP to make a dramatic turn to the left and adopt more militant policies in favour of working people, publicly calling on Alexa McDonough, who had led the party in the past two disappointing elections, to resign. Sid Ryan, the leader of the Ontario Division of the Canadian Union of Public Employees, one of the largest unions in the country and one of the unions which has suffered from job losses from massive cut-backs imposed by the NDP wherever it has formed the provincial governments, gave his support to Hargrove, saying that the NDP was now "moribund".

This debate was not just a one-night phenomenon. It has shaken the party to its core. Over the course of many months, Hargrove – wherever he could get an audience – campaigned to have the leadership removed. He appeared on many TV public affairs programmes, debating the right wing of the party about the need for a more militant anti-capitalist position, raising the idea of nationalisation of the major financial institutions, the first time that has been done in a popular way in Canada in many years. Many militants and leftists began to take notice of this important political debate which was about the kind of policies necessary to deal with the social and economic problems created by capitalism and what kind of political party would working people need to run the country.

A NEW OPPOSITION FOR A NEW PARTY

Opposition to the leadership took on a more dramatic and organisational form, which placed a question mark over the future of the NDP, when Robinson, Davies, Judy Rebick, a well-known writer, feminist and socialist, Jim Stanford, an economist and researcher with the CAW, along with other prominent intellectuals and activists, began a campaign to replace the NDP with a new, more radical, left party, but which would encompass the NDP. They sought to involve the activists of the new social justice and anti-globalisation movements in its construction, around the ideas of participatory democracy, inspired by the experience of the Workers Party of Brazil and the citizens' participation budget process of Porto Alegre. They called their grouping, the New Politics Initiative (NPI), (www.newpolitics.ca). While more radical than the NDP, - especially on Quebec – the NPI did not take a clear position for socialism. Hargrove did not formally commit himself organisationally to the NPI, but it was clear in various debates that he and the CAW leadership team favoured this new opposition to the McDonough leadership.

The NPI urged political activists, both inside and outside the party, to struggle for their perspective. They hoped the crisis in the NDP would begin a process that would lead to the creation of a new political party on the left in Canada. The NDP, they said, because of its manner of functioning and the alienation the youth activists feel towards it, had been unable to effectively confront the neo-liberal agenda of the governing Liberals and had exhausted its usefulness. Many – and not only on the left – saw this as the only way to shake up the leadership and make fundamental changes to the party. More than sixty constituencies supported the NPI resolution.

Over 1000 people endorsed the NPI's "Vision Statement", a radical left critique of Canadian capitalism with specific proposals to transform society, reaffirming the left's important role in "challenging the right of the wealthy to oppress and exploit, demanding that our collective knowledge and talents be used to raise up human standards, rather than enriching the few… " At the various meetings that were organised by the NPI, especially in the Toronto area, approximately half, when asked, said they were not members of the NDP. The new opposition grouping became the focal point for a major discussion in the working class, especially among political activists.

THE NDP CONVENTION

The leadership of the party went all out to mobilise their supporters for the convention in Winnipeg in November 2001, to turn back this new challenge. But this does not fully explain the reasons why over 1400 people turned out, twice what had been anticipated. There was genuine popular interest in the party about the debate the NPI had initiated.

There was also concern about the future existence of the party and whether a much talked about "renewal process" would solve anything. The leadership had begun a "renewal process" in February, 2001, in an attempt to deal with the party's internal crisis and to show they were indeed responsive to criticisms of their failures. A "renewal" committee was appointed to travel the country asking members and supporters how the party could become more relevant. The leadership claims written questionnaires were filled out and eighty meetings were organised in which a total of 10,000 people participated. Robinson and Stanford say the NPI was involved in the "renewal" process and had met with the "renewal" Steering Committee, but this participation was not organised and was not widely known in the ranks of the NPI. In most respects, this NDP "renewal" was a top-down process, well structured and closed to critics from the left who had no formal participation in the process. In Toronto, at one large meeting, even speakers from the floor were pre-selected. Many activists in the party expressed suspicion of the "renewal" process, having been through similar exercises in the past. They saw it as a cosmetic exercise by the party brass to "re-brand" the old product without seriously examining the policies that had led to the crisis in the first place.

The final "renewal report, in the words of NPIers Robinson and Stanford, "echoed many of the themes that have been stressed by the New Politics Initiative" and the need to reach out to "much or most of the new energy", which is outside the NDP, "and position itself more clearly as a party of the left." But the bulk of the report is a gathering together, in survey style, of a multitude of opinions and views by members and supporters without any clear direction being given to the party. The leadership committed itself to keeping this "renewal process" going, at least for another year. "We are a party of continual renewal," McDonough stated, making the process seem to be everything and yet nothing at the same time. The new president of the party, twenty-four year old Adam Giamboni, however, made the point of attending the meetings of the NPI and the Socialist Caucus to assure them they would be involved in the next phase of "the renewal".

THE QUEBEC SUMMIT AND THE WAR

Shortly after the beginning of the "renewal process" and to ward off criticisms of its lack of connection to the growing anti-globalisation movement, the NDP leadership had made a prominent display in April of going to Quebec City to participate in the People's Summit during the popular protests there against the Summit of the Americas But they advocated a program of protectionism – "we must protect Canadian jobs".

After Sept 11th, they opposed the bombing of Afghanistan, in a major departure from the policies of other social-democratic and Labour parties around the world. This was a major debate at the convention. While the NDP position was weak in calling for some type of United Nations' solution to the war, the main focus of the resolution was clearly against American imperialism, which is how the bulk of the delegates understood it. The delegates and the NDP Caucus in parliament also opposed the severe curtailment of civil liberties in Canada when Bill C36 and anti-immigration rules were pushed through parliament, measures which are even more reactionary than similar legislation enacted in the United States and Europe. McDonough had called for "an immediate end to the U.S. led military action and an end to the Canadian participation in this action", but paradoxically, in a block with the right-wing parties in parliament, the NDP voted – to the dismay of many of its supporters–for the government's military budget, going so far as to criticise the ruling Liberals for not making it larger! On December 4, she committed NDP support for the Canadian government's sending of Canadian troops to Afghanistan, totally undermining the NDP's credibility on the war issue.

The NPI was poorly organised at the convention – something its leaders readily admit. It performed far below its potential, a combination of the lack of experience on the part of its supporters and the fact that some of its key leaders were not members of the party and therefore not delegates. But the NPI also a lacked a political will to seriously struggle for its positions. In a sense, similar to the NDP leadership it opposes, its trenchant criticism of capitalism notwithstanding, it seems hesitant in coming to terms with the class nature of Canadian politics and the need for the working class as an organised force to remove the ruling class from power in order to achieve emancipation.

"The main problem on Canada's left is not a lack of good progressive policy ideas… ", Robinson and Stanford stated in an article prepared for the convention. "The main problem, rather, is structural: the chasm that has emerged between the work of electoral-oriented parties and the day-to-day work of activists and campaigners who are organising for social change every day of the year. The NPI is focused on that structural issue. In particular, our goal is not to shift the NDP to the left: our goal is to build a more effective, democratic, and connected party that consequently becomes more successful … " In the eyes of the leaders of the NPI, the main problem with the NDP is not programmatic, but that it lacks a democratic and participatory process. They thereby avoid the need to seriously confront the party leadership politically and therefore gave little thought to participating at the convention in the floor discussions on the various policy resolutions on the floor – many of which reaffirmed the current conservative policies of the party – and which would have allowed the NPI grouping to define itself more clearly for the delegates. As a result, it was not clear where the NPI stood programmatically – although its leaders stated they wanted "a more left party," that was "not part of the mushy middle". Its main complaint was that the party was not sufficiently oriented towards the new social justice activists who make up the extra-parliamentary opposition, without making clear to the delegates what this would mean in practical terms.

The NPI, even though it held very successful and enthusiastic meetings of its supporters off the convention floor, provided weak floor leadership, if any to the delegates who supported the NPI positions. They often had difficulty understanding what was expected of them. As a result, the true strength of the NPI was not accurately reflected in the convention. Instead, others, who prior to the convention had been excessively criticising NPI – such as leaders of the much more insignificant Socialist Caucus, and who had distanced themselves from the NPI resolution calling for the new party, gave the appearance – to those who did not know any better – of representing the NPI! In a debate that was factionalised by the leadership of the party – who pointed to their own stand on Afghanistan and their trip to Quebec City as evidence that they were not part of "the mushy middle" – the NPI resolution calling for a new party was defeated, gaining 37% of the votes. But an important part of that came from some the unions, including the CAW delegates voted as a bloc for the NPI.

The Socialist Caucus made some telling points at the convention. For example, they very cleverly exposed the hypocrisy of the NDP leadership who complain about a lack of democracy in the electoral arena and who demand proportional representation in Parliament, but who deny minority representation to political minorities on the leadership bodies of the party. However, the Socialist Caucus appeared to have difficulty adjusting to the new situation in the NDP with the rise of the NPI and the opportunity this represented to engage the membership in discussion on a broader level. Moreover, they could not seem to make up their minds whether or not they truly supported the NPI; they claimed to be giving it "critical support", but this was long on criticism and short on support, fooling no one. The NPI's caucus meetings at the convention were large – over 400 at one meeting–compared to the handful who attended the Socialist Caucus events. In the leadership election, the Socialist Caucus' candidate to replace Alexa McDonough received 15% of vote.

The convention was structured in a way to make it difficult for the delegates to have an adequate political discussion. Much of the time was taken up with videos and guest speakers, a frustrating experience for many delegates. But Socialist Caucus leaders acted on the convention floor in a manner that increased this frustration and made it easy for the leadership of the NDP to isolate them. For example, when the convention opened, Socialist Caucus delegates challenged the agenda, despite request from the NPI that they not do this. The NDP leadership had allocated two-and-a-half hours for the "renewal report" discussion – still insufficient–but to the bewilderment of many delegates, the Socialist Caucus leaders argued that this be reduced to forty-five minutes – "so that more important resolutions can be discussed" – thereby proposing to virtually kill one of the most important discussions of the convention.

To the right of the McDonough leadership, the pressure group, NDProgress, led by Peter Stoffer proposed that the NDP break its connection to the unions by changing their representation at conventions. They also supported a proposal, floated by the leadership, to remove the constitutional right of delegates in convention to elect the leader. This MP, before it had become politically embarrassing, had been an open advocate of Tony Blair's "Third Way" pro-capitalist policies. In a compromise the party leadership backed a hybrid version of Stoffer's proposal on leadership selection – a referendum of the membership, with 25% of the vote coming from the trade unions. The leadership was unable to explain how this will work in practice. The constitution was amended to reduce the percentage of union delegates at conventions from 40% to 25%.

AFTER THE CONVENTION

At the conclusion of the convention, there was consensus among NPI supporters that it should stay on a dual track: continue working politically both inside the party and outside the party. How this will work out in practice, remains to be seen, and it must be noted that preparing for the NDP convention provided the focus in the months before, for much of the activities and discussion in the NPI. There was no support for the idea of splitting from the NDP and forming a new party. Most of the NPI leadership agree that if there is going to be a "left" alternative to the NDP, it should have a reasonable prospect of becoming mass-based. Significantly, and in a new spirit of accommodation, three leading members of the NPI–selected by the NPI – have been added to the NDP "renewal process" Steering Committee.

More importantly, the political situation in the country post-Sept 11 has shifted to the right; it is still unclear by how much. This will have to be discussed by the NPI. Most of the leadership of the national trade-union has been silent on the war, with the notable exception of the Ontario Federation Of Labour. The economic recession has deepened, with mass lay-offs in lumber, the air-line industry and auto. There has been a large jump in the unemployment numbers across the county. There is also a discernible subsidence of the anti-globalisation and social justice movements. Linking up with this movement was a key component of NPI strategy. In addition, the CAW is now in the process of re-evaluating its long relationship to the NDP with the possibility of disaffiliation on the table. Determining whether this reflects an expression of de-politicisation or a new phase of political radicalisation by this important union will also have to be discussed. Regional conferences of NPI supporters to work out the organisation's perspectives will take place in the coming months.

THE NEW DEMOCRATIC PARTY IN THE PROVINCES

In Canada's English-speaking provinces the NDP has had some success, forming the government in several, including Ontario in the early 1990's. It barely exists in Quebec, because of its historic inability to deal with the national question. The leadership supported, in violation of NDP convention policy, the Liberal government's Clarity Bill, a legal manoeuvre challenging Quebec's right to determine its future in a referendum, thereby confining the NDP to the political margins there. It presently forms the government in Manitoba and has held power in Saskatchewan for many years, where it now survives through a coalition with the Liberal Party. In both these provinces it has been the willing servants of the bond-holders and the ruling class, implementing "in a kinder way" the neo-liberal agenda with cuts to social services including the closing of over fifty hospitals in Saskatchewan. To the dismay of many in the labour movement, the Manitoba government has recently floated the idea of a two-tier minimum wage whereby thousands of workers would be working for less than the existing minimum wage. The respective provincial federations of labour have become disenchanted with both these Provincial NDP's neo-liberal policies, especially the drive by the Manitoba party to distance itself from the unions by enacting legislation that prohibits financial contributions to political parties during elections, both by the large corporations and the trade unions, thereby placing an equal sign between the unions and the large capitalist enterprises. The NDP was recently tossed out of office in British Columbia where it had alienated the labour movement and much of the working class by pushing through massive lay-offs in the public sector. It lost 77 seats to a far-right Liberal party. It now has only two sitting members, one of whom, Jenny Kwan, is a supporter of the New Politics Initiative.