frontline 6

Argentina, a revolution in the making

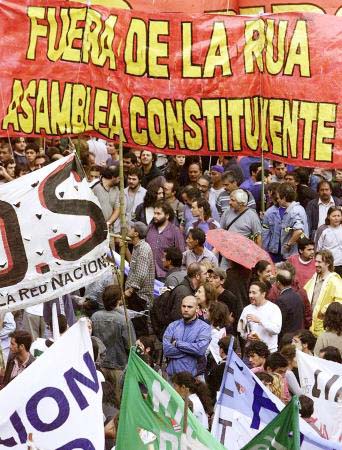

The economic and social catastrophe that has befallen Argentina is the clearest indication to date of the utterly disastrous effects of slavishly applying the neoliberal policies of the IMF and the World Bank. But the mass revolt of the working class and people of Argentina also shows that it is possible to reject these policies and to bring down the governments which impose them. In this article written in mid-January, Argentinian socialist Virginia de la Siega describes the revolutionary events taking place in her country. Events since then have confirmed the breadth of the mobilisation of the Argentinian people and the precarious position of the Duhalde government, caught between the hammer of its own people and the anvil of imperialism. We will carry further material on Argentina in future issues of Frontline.

On January 13th 2002, unreported by the press, there took place in Parque Centenario, in the heart of the city of Buenos Aires, the first meeting of representatives of the Regional Assemblies of the Federal Capital and some districts of Greater Buenos Aires. There, the representatives of the different neighbourhoods of the capital met for the first time with those of the province of Buenos Aires, with representatives of factories which are on strike and with those of the "motoqueros" (young people who work on their motorbikes for a private mail service) the heroes of the battle of Plaza de Mayo. One by one, they put up the basic demands voted at the different assemblies: the non-payment of the debt, the resignation of the Supreme Court, the return of the savings confiscated by the government, immediate elections, annulment of the 13 per cent discount on pensions, the immediate restitution of services like electricity, telephone and gas to those who had them cut off because they could not pay the bills. Those present also agreed to participate in different activities and marches against the government, the members of the Supreme Court, the journalists who support the plan of the government, the multinationals, and in support of those workers who are at the moment striking or taking up all sorts of struggles to get their salaries paid or to prevent the closure of their workplaces. A special mention of support to all those activities launched by the relatives of those killed by the forces of repression was made.

The revolutionary process that reached its first peak on December 19-20 with the overthrow of the democratically elected government has kept moving forward. The first attempt of the Argentinian masses to determine themselves independently from bourgeois parties has started. Where it will end we cannot foresee. The Argentinian working class has started a way that will be long, difficult and hard, but we do not doubt that it will have the support of all those around the world who want to finish with the oppression of capitalism. The anti-globalisation fighters all over the world have to see the struggle of the Argentinian people as their own struggle. In the streets of Buenos Aires and of the main cities of Argentina people are questioning with their very lives the idea that "there is no other alternative", and creating this alternative with their own blood.

The question is: how did this come to happen?

THE NEOLIBERAL LABORATORY

The story begins on March 24, 1976, when the military dictatorship took power with the support of the US government. The purpose was to do in Argentina what Pinochet had done in Chile: transform it into a laboratory for the application of the neoliberal plan. It is to the merit of the Argentinian working class that despite the 30,000 workers and students who were assassinated, the full plan could never be implemented. However, the Minister of the Economy of the military regime, Domingo Cavallo, took one measure that would prove fateful. To the debt that the State had acquired with the IMF and other foreign creditors under the military regime, he added the private debt of the Argentinian bourgeoisie. Finally, the dictatorship was brought down, but the debt it had created remained.

The president elected in 1983, Raul Alfonsin, tried, also unsuccessfully, to impose the neoliberal plan. One general strike after the other made it impossible to implement his privatisation plans. As a consequence, in 1989, financial capital launched a process of hyperinflation. The people, desperate, looted supermarkets demanding food. The government fell.

Carlos Menem, the newly elected president, took power promising to change things. However as soon as resistance to the process of privatisation started, a second hyperinflation crushed it. His Minister of the Economy, Domingo Cavallo — sound familiar? —, under the instructions of the IMF and the World Bank, devised "convertibility", the pegging of the peso to the dollar. This mechanism, which was "sold" to the Argentinians as the only way to end inflation, was combined with the application of all the neoliberal measures that had been resisted for over a decade. Now it was necessary "to go global", to open our market to competition, to export what "we could produce best" and import the rest.

THE FAILURE OF THE NEOLIBERAL MYTH

The illusion that 37 million people could live by exporting primary products (aluminum, grains, energy, etc., all industries that do not employ high numbers of workers), while opening the market and allowing imports to sweep away the old industries which employed most workers, lasted several years. Little by little, Argentina became a country where nothing was produced. In seven years, unemployment leapt from 6 to 16 per cent, salaries lost 32 per cent of their purchasing power, 45 per cent of the population was living below the poverty line. While the country was sinking into poverty and despair, Argentinians were told that all these measures were necessary so that foreign capital would keep investing in the country.

By 1999, the country was on the brink of default. A new president, Fernando De la Rúa, was elected, once again, with the promise that he would revert the neoliberal measures taken by Menem.

Very soon, Argentinian workers realised that those promises would not be fulfilled. The answer was a renewed wave of strikes. At the beginning, the strikes were half-hearted. It is no wonder. They were called by the same trade union bureaucracy that had refused to fight against privatisation under Menem's government. But as the economic situation deteriorated, the workers became more and more militant. Two ministers of the economy were forced to resign. Finally, Domingo Cavallo was called in once again "to solve" the problem. And in he came, with the full support of the IMF and the World Bank, who could not think of anybody more capable of defending their interests.

The consequences of his months in power were far beyond the wildest nightmares of both Argentinians and the world's financiers. In a desperate attempt to continue the payment of the foreign debt, he reduced salaries and pensions by 13 per cent. As that was not enough, he first forced all salaries to be paid through banks and finally confiscated all deposits establishing a limit to the money that could be withdrawn in cash from current accounts per week and per month. Savings accounts and deposits were frozen. The Argentinian economy, which had been suffering from recession for almost four years, came to a halt.

THE WORKING CLASS IN ACTION

On December 13, after a series of strikes called by teachers, railway and municipal workers, there was a massive general strike against the economic plan. On the same day, the municipal workers of Córdoba, the second city of the country took over and looted the Town Hall.

The following day, December 14, men and women, with their children by the hand, asked for food at the door of supermarkets. Where the owners refused to give it, the people, desperate, attacked the supermarkets. There were food riots in Rosario, Mendoza and Entre Ríos. In the following days, these actions spread to the rest of the country.

On December 19, De la Rua made a speech on television to declare the state of siege. Suddenly, without any summons, pots and pans started clanging in different neighbourhoods of the Federal Capital and other cities in the country. The first "cacerolazo" had started. Soon, the people started leaving their homes with their children, gathering by the hundreds and thousands, and shouting: "You can stuff the state of siege up your arse!", "No more radicals or Peronists!" and marching towards Plaza de Mayo, to the House of Government. By 11 p.m. there were 80,000 people gathered in the square. Argentine flags could be seen everywhere. The workers and the people of Argentina had met many times in Plaza de Mayo to demand the resignation of military dictatorships. For the first time in their history, they were now demanding the resignation of a democratically elected government.

The government gave the police the order to attack. They waited until the early hours of the morning to carry out the order. The first people to be attacked were the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo—the mothers of those who were killed by the dictatorship—, some priests who were praying in the square, and the families who refused to move. But the heaviest attacks came the following day. Most of the people were killed between 3 and 4 p.m. Immediately, the "motoqueros" took it upon themselves to defend the demonstrators, disorganising the ranks of the police by launching their motorbikes against them. They were helped in this task by the organisations of the Left. Soon it became evident not only that the police were not shooting rubber bullets but real ones, but that policemen dressed as civilians were shooting at the demonstrators. Two "motoqueros" were killed, and in total seven people died in the confrontation in Plaza de Mayo. The struggle spread to different parts of the city. Finally, after hours of fighting and 32 people killed, De la Rúa resigned.

On December 23, Adolfo Rodríguez Saá, a Peronist, was elected president by Congress. His task: to call a new presidential election for March 3, 2002. His promises: non-payment of the foreign debt, keeping "convertibility", allowing people to withdraw their savings, one million jobs, annulment of the law that amnestied the military who were guilty of crimes against humanity...

However, none of this was to be. On December 28, the Supreme Court ruled that it was legal for the government to prevent people from withdrawing their savings. On hearing this, thousands of people marched to the building of the Supreme Court demanding their resignation. In the evening, once again, without any summons, the pots and pans started clanging and around 80,000 people marched to Plaza de Mayo chanting against the government. At around 3 a.m., when the demonstrators tried to march against the House of Government, the police attacked. The demonstrators retreated and started marching towards Congress. Once there, they managed to get in and destroy whatever they could lay their hands on. Cornered by the demonstrations and without the support of his party, Rodriguez Saá finally resigned on December.

A PRESIDENT ELECTED BEHIND THE BACKS OF THE PEOPLE

On January 1, 2002, Congress met once again to elect Eduardo Duhalde president. Duhalde had been the Peronist presidential candidate defeated by De la Rua in 1999.

This time, the demonstrators who had gathered outside the Congress to repudiate this election were not attacked by the police. On the contrary, the police remained motionless while gangs of thugs of the apparatus of the elected president attacked their political opponents. In his presidential speech Duhalde warned that the country was in a situation of default. However, about what really worried people: their savings, the future of the debt, the future of the peso, nothing was said.

Finally, on January 9, the measure everybody had been expecting was taken: Argentina's peso was no longer pegged to the dollar. It was to undergo a 40 per cent devaluation. Those who wanted to buy dollars, however, would have to pay the price of the free market (at the time of writing this article the rate is one dollar to two pesos and it is thought that the dollar may reach a rate of three pesos). Loans and services, most of which had been agreed in dollars, were to be transformed into pesos, and the banks and the multinationals would suffer the losses. This provoked the anger of multinationals, who own around 75 per cent of the banks and all the privatised services.

However, the problem was what to do with people's savings. The government was frightened, thinking — not without reason — that if people were allowed to withdraw their money, they would immediately buy dollars to preserve their savings. Therefore, bank deposits were not to be freed until ... 2003 and 2004, and then, only in monthly installments. On the evening of January 10, the first pots and pans started banging again. The first "cacerolazo" against Duhalde's government was taking place.

Finally, after a fortnight that felt like a year, under the relentless attacks of a population that everyday in a different place of the country launches a "cacerolazo" against foreign banks, the multinationals and the government, Duhalde decided to partially release people's savings. Will this be enough to stop the revolutionary process that the workers and the people of Argentina started a month ago? Not very likely.

WHAT IS TO COME?

The revolutionary process in Argentina took imperialism unawares. With their head in the Afghan war and the recession that is hitting the world economy, they thought that the Argentinian crisis had been so long coming that the danger of economic "contagion" had been avoided.

Now, however, the cleverer analysts are beginning to realise that the process that is under way in Argentina may have political repercussions that they had not thought of. Not only have the workers and the people of Argentina brought down a democratically elected government, but also, for the first time, they are in the streets and shouting to the world that neoliberalism means misery and starvation. That the peoples of Latin America may soon begin to identify with the struggle of the Argentinians is shown by the fact that their governments hastened to support Duhalde and defend his case in all international financial bodies.

It is a fact that people in the Federal Capital and in other parts of the country are beginning to organise themselves in weekly assemblies where everything is decided by vote. The experience described at the opening of this article is to be repeated every week. The outline of a revolutionary programme can be seen in the proposals that have been put forward. However, this does not mean that the way to the revolution will be easy. The fact that people are beginning to organise themselves and are against imperialism, the multinationals and paying the foreign debt does not mean they have finished their experience with capitalism. Many still believe that "capitalism with a human face" is possible. Others even think that with their demonstrations they are helping the government to fight against the multinationals. Taking advantage of this confusion, the government is aiming at dividing the struggle. Special plans have been announced to aid those who are unemployed and their families, and attempts are being made to "de-freeze" savings in an attempt to control the "cacerolazos". Whether the people will fall into this trap is another matter, but unless socialism, the only feasible solution, is presented to the masses and the workers, and taken up by them, the ranks of those who struggle may begin to dwindle, weakened by the lack of a solution to the catastrophe that has fallen upon them.

In this situation, the role of the Left is of the utmost importance.

In October 2001, for the first time in history, the vote for the Left reached 7 per cent. In December, for the first time in almost 25 years, an alliance of the left and independent students' organisations won the leadership of the Student Union of the University of Buenos Aires, a stronghold of the Centre-Right. This is a sign of what may come if the Left unites.

During the insurrection of December 19-20t and the days that followed, the prestige of Luis Zamora, the first Trotskyist MP elected in Argentina, grew, as he was one of the few that took part in the events. Zamora had been elected again to parliament in October 2001, outside all party structures. Old and new activists are gathering around his movement, as well as joining different left-wing organisations. This would be the time for the Left to unite and lay the basis for the party that Argentinian workers need. Will the organisations of the Left be up to what is required of them?

But no matter how heroically the Argentinian masses may fight, if an international movement of support to their struggle is not built, they will be drowned in blood and fire. We are only at the beginning and thirty-two people have already been killed. We cannot assume that the government and the imperialist powers will take it calmly if the revolutionary process deepens and strengthens. This is what talking about revolution means. The Argentinian masses have proved through their history that they are willing to pay the price. Will the masses of the workers of the world support them in their struggle?

Notes on the Argentinian Left

The two main political parties in Argentina are the Peronists, the movement founded by populist president Juan Peron in the 1940s, and the centre-right Radicals, the traditional bourgeois party. Other mainstream parties are the centre-left FREPASO, which stood in an alliance with the Radicals at the last elections, and the recently founded Alliance for a Republic of Equals (ARI), a split from the Radicals whose main theme has been the fight against corruption.

The Left in Argentina is fairly strong but fragmented. Three organisations are descended from the Trotskyist Movement towards Socialism (MAS) founded by Nahuel Moreno, which was a powerful force in the 1980s before suffering a series of splits: these are the MAS, the Socialist Workers' Movement (MST) and the Workers' Party for Socialism (PTS). There is a fourth Trotskyist organisation, the Workers' Party (PO). The formerly pro-Soviet Argentinian Communist Party (PCA) has aligned itself with Cuba since the collapse of the Soviet Union. In last October's elections there were three lists: the United Left (a bloc of the MST and the CPA), an alliance of the MAS and the PO and a PTS list. Luis Zamora, who was elected as an MP for the united MAS in the 1980s but is now a member of no organisation, formed a loose movement ("Self-determination and Freedom") and stood only in Buenos Aires, where he obtained 10 per cent and was elected as an MP along with another representative of his movement, as was Patricia Walsh of the United Left. The total of all these left list was one million votes, 7 per cent. The elections, in a country where voting is compulsory, were also marked by a 25 per cent rate of abstention. Equally significant, 21 per cent of those who did vote, voted blank. The triple phenomenon of abstentions, blank votes and the big vote for the Left represented a massive rejection of the mainstream political parties and can be seen as a harbinger of the revolt that was to erupt two months later.